Teaching a child to read isn’t as easy as you may think. There is a TON of research on how children learn to read and many, many programs available to both parents and the public school system. Children who don’t have a reading disorder will usually learn to read despite poor reading instruction. However, children with dyslexia suffer grave consequences if not given explicit, systematic instruction as part of their reading lessons.

The debate on which methods of reading intervention are best and which ones should be avoided like the plague are a post for another day. The reason I bring it up is because regardless of which method of instruction children are getting there is one area of reading instruction all children are exposed to at some point in their academic career and it’s critical they are taught this properly.

The problem is that most people do it wrong.

Not because they don’t agree with what’s right or because they are lazy. It’s simply because most people don’t know better. Parents and teachers included.

I’m talking about speech sounds. The fancy word for speech sounds is phonemes.

What are Phonemes?

Phonemes are the smallest unit of meaningful sound represented in our speech. Phonemes are the different sounds you hear in each word.

For example, the word “CAT” has 3 phonemes…../k/ /a/ /t/.

Three sounds/phonemes and three letters. Seems easy enough, right?

The problem is that the number of phonemes and the number of letters in a word are often different. For example, the word “ship” has 4 letters but only three phonemes…./sh/ /i/ /p/.

The letters “sh” are a digraph. This means they are two letters that make one sound. We have four digraphs in English: “sh” as is ship, “ch” as in chip, “th” as in thorn or these, and “wh” as in when.

Did you notice I gave 2 examples for the “th” digraph? That’s because sometimes we say “th” with our voice off as in the word thorn and sometimes we say “th” with our voice on as in these.

More on voicing later. For now, let’s go back to sounds and letters.

To make matters even more confusing we have trigraphs as well. That’s when three letters make one sound! Think about the word match. Match has five letters but only three sounds

/m/ /a/ /tch/.

If that’s not enough to convince you that learning to read is complicated. Think about this…I’ve given you examples of words that have letter combinations that match the sounds we hear.

Sometimes these things don’t match up! For example, consider the word “of”- this is a word that seems so basic but is really difficult for kids with dyslexia because neither of the letters matches the sounds in the word!

Think about it then say “of” aloud. What two sounds did you use?

/u/ /v/, right? And that’s exactly how almost all of my dyslexic students spell “of”. They try to sound out the word but in this case it doesn’t help them achieve the correct spelling. So the word of has two sounds and two letters but they don’t match up to the letter-sound relationships we teach children in the early grades.

What Parents and Teachers Can Do?

So, if you are a parent working with your child at home what can you do? Reading gets complicated but it’s not because English is some crazy unpredictable language. In fact, according to Denise Eide in Uncovering the Logic of English: A common-sense Approach to Reading, Spelling, and Literacy 98% of English is rule-based.

When these rules are taught to children with dyslexia using explicit, systematic instruction in a way that is cumulative and multisensory they learn to read!

Many teachers, schools, and parents are beginning to catch on to the benefit of structured literacy and children and definitely benefitting.

Here’s where I see the breakdown in instruction occurring most often. Many times the sounds are being modeled to the child incorrectly and it’s making learning to read much more difficult than it needs to be.

Let\’s go back to the word cat. This was an easy one, remember? Three sounds and three letters that matched up well.

I want you to slow down and say each sound in the word cat aloud. Ready? C- A- T.

Now, did you say cuh-a-tuh? Or did you say c-a-t?

If you’re asking yourself what the difference is then my guess is you said it the first way.

And that would be the wrong way.

You see, when we say the sounds for “c” and “t” we should not be using our voice. I want you to whisper the word cat. When you whisper the word, your voice is off. Now say each sound in the word cat again and whisper the sounds for “c” and “t”. You should only turn your voice on for the vowel.

That’s the correct way to produce those sounds.

Why Does this Matter?

I have a child I’m working with right now and her mom attends every session. This mom is a parent dedicated to helping her child at home and wants to make sure she knows what to do at home between each session. When I started teaching her child the difference between cuh-a-tuh and c-a-t, mom was shocked that she had never thought about the difference before then admitted “I’ve been doing it wrong at home”. It’s not because she wasn’t doing her very best to help. It was simply that no one had taught her any differently.

Her daughter is going into second grade and reads at a Kindergarten level. Her mom came to me concerned that no progress was made during first grade. We’ve been working on proper production of phonemes for letter-sound correspondence (for both mom and daughter, lol) and the child is now making weekly progress and mom is thrilled!

That is an example of exactly why we (SLP, teachers, and parents) MUST teach speech sounds/phonemes correctly.

If we teach children that the letter “c” is paired with the sound “cuh”, not “c” (or /k/ as phonemes are represented by linguists and SLPs) then children will struggle sounding out the word cat because their little brains will be trying to add a bunch of sounds that don’t belong: cuh-a-tuh vs. cat.

Loud Sounds vs. Whisper Sounds

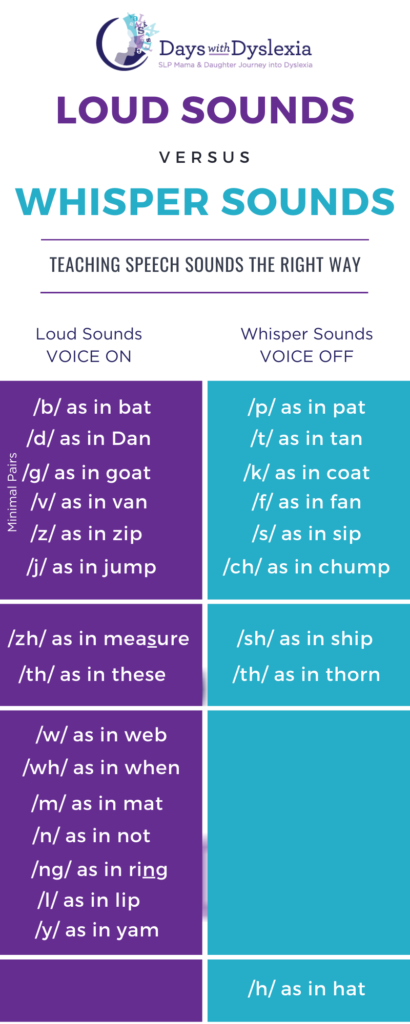

Take a look at this chart I created to help you with voice on or “loud sounds” vs. voice off or “whisper sounds”.

The column on the left represents all the phonemes in English that we produce with our voice on. When you use your voice you are engaging your vocal folds; this is what serves and the vibratory source to create the sound. If you hold your hand to your throat while making noise you can actually feel the vibration. Try it while making a long /s/ sound then a long /z/ sound.

You will feel your throat vibrate while making the /z/ but not the /s/.

Back to the chart….You’ll notice that each column is broken down into 4 sections. The top section has an additional label of Minimal Pairs. This means the only things that changes when saying those sounds or the word examples provided is the voicing in the featured phoneme.

There are three ways we can modify phonemes and when only one of those features changes, it’s called a minimal pair. This is simply because there is only a minimal difference between the sounds. Check out my quick video on 3 Things You Must Know to Help Your Child with Dyslexia for a description of all three ways we modify speech sounds.

In the second set of words, the phonemes themselves are minimal pairs but there are no real words that can serve as minimal pair examples. The third set of phonemes are all voiced but have no minimal pair for comparison and the bottom set contains a phoneme that does not use the voice and has no voiced minimal pair.

This may seem confusing but if you read through the list several times and practice saying the sounds and words aloud this should all make more sense. If it doesn’t, please let me know in the comments and I’ll try to clarify further.

If you’d like a printer friendly copy of the Loud vs. Whisper Sounds chart, you can download it here.